Of the glamour of primary health care, and clinical courage

Reflections from a physician on what primary healthcare means to her

Till 5 years ago, my work as a pediatrician and public health physician was quite far away from primary health care. Be it working in a tertiary care hospital, or a training institution, or being part of community-based research, there was a clear distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

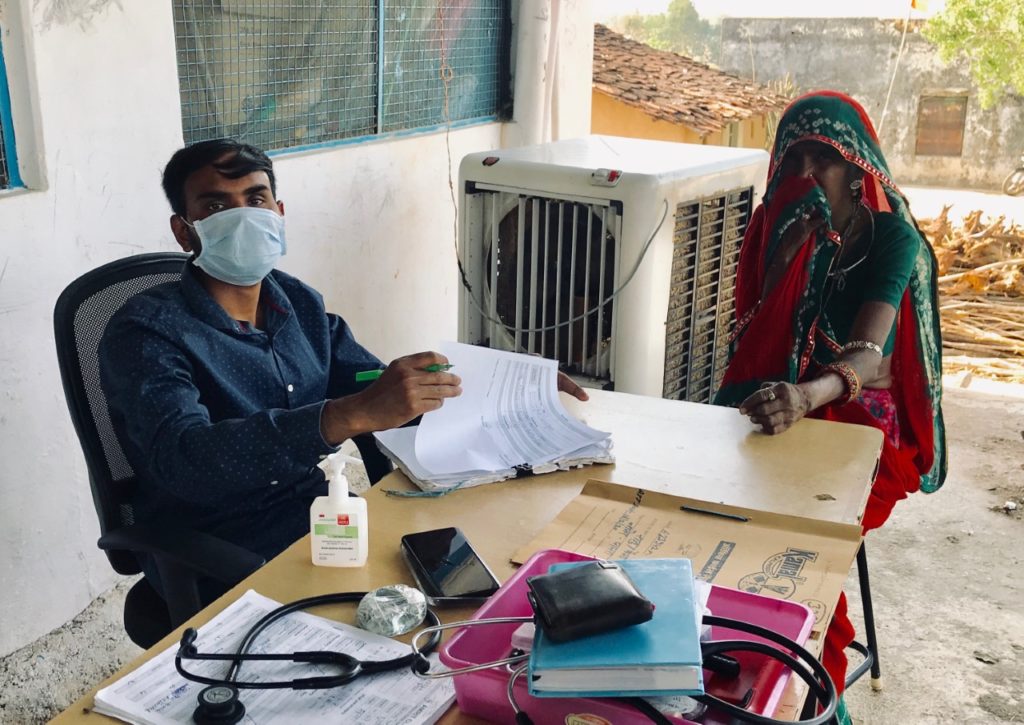

My immersion in primary healthcare began 5 years ago, when I started working in deep rural, tribal areas in southern Rajasthan. The early days were so difficult- how do you manage a hypertensive emergency, rheumatic heart disease with failure, antepartum hemorrhage, and more, all at once? My training was in pediatrics, I had last seen adult patients over 20 years ago. I was nervous as anything!

Fast forward 5 years, I understand the primary healthcare space much better. “What is it like to work in primary healthcare,” I’m often asked. Well, here goes.

Primary healthcare is full of challenges

A normal day can bring an adolescent with diabetes and ketoacidosis, a severely malnourished child with severe pneumonia, many men with advanced tuberculosis, and a lot more. Many of the sick who actually need hospitalization in a tertiary care hospital, often 70-100 kms away will say- “We cannot go so far. Please do what you can”. And you do. There is little choice anyway. And most of the times, it works.

Many times I hear people say that primary healthcare is about ‘choti-moti bimari’ (minor illnesses). It is much more than that, I want to tell them.

If you apply your knowledge and experience, check your facts quickly, connect with experts when needed, you will do well

You conduct a delivery, in a few hours she starts bleeding- “as if a tap had opened”. You see a very sick child with hyperpyrexia, falciparum malaria. And young men with advanced silicosis and hypoxia, lungs badly damaged. How do you manage such diverse conditions, where survival hangs by a slender thread?

You check your guidelines quickly. Maybe call up an expert from the relevant domain, one who is part of a group which understands and also values your work. And you see how a hopeless situation is salvaged. The biggest thing is to act. Almost 3 decades ago, when I was starting my residency in pediatrics, my guide Dr. Miglani, who was one in a million, told us all- ‘Just keep working. What you learn while working, you will remember for the rest of your lives’. Timeless wisdom this. Something to always remember.

The fruits of success make all the effort worthwhile

One of my most clear memories is of a young man with tuberculosis, who was only skin and bones when he first came to us. He could not get up from the bed, and his family had given up all hope. It is difficult to count the number of visits we made to his household. Supporting him with medicines, also food, counseling and encouragement. In few months, the transformation was very visible: with a weight gain of 25 kilos, he recovered from TB and started a new life.

We are sometimes told that (as a team) we work very hard. When there are such tranformations along the journey, no effort is too much. Their smiles seem to make all aches and tiredness disappear.

A physician is very important, but it is a team which makes a difference

Like the story of the young man above, there are countless others. Where it seemed that the person would not recover from the illness, he or she did; where a father was not ready for referral of his young girl with severe anaemia, not only did he agree to take her, but also donated blood- something still rare in these parts of the country.

I now understand that a physician alone cannot bring about such transformation. Nurses and health workers are way better at building a rapport and trust, identifying questions and fears among the people, and resolving them. This is engagement at a truly equal level, something us doctors would do well to learn.

I am able to see a patient not in isolation, but as a part of a whole

I am able to understand better the person before me, also their wins, and battles. The father of a young girl, his fourth daughter, so determined that she gets well, as “boy or girl, they are both our children, no?”. The pregnant woman with severe asthma, who uses firewood for cooking, as she gave her gas cylinder to her sister, who is studying nursing. Why did you not study, I ask her. “Because I had to take the goats for grazing”, she says. The severely malnourished girl who was so irregular in her visits to the clinic would have irritated me earlier. I know now that her mother has a disability so finds it difficult to carry her. And her father had gone to Ahmedabad for work.

Why are these stories important? They humble me, inspire me. Many times, it is these which make me pull up my socks and pep up my strength to go on.

Finally, what is it that works?

Till few years ago, the physician in me naively believed that it is the medicines which do the work, or most of it anyway. I think a little differently now. The patients need medicines, surely. Also need understanding, upholding their dignity, and love and care. From their family and friends, as well as the healthcare providers.

During a recent discussion on primary healthcare spanning different continents, a very experienced primary care physician spoke of the ‘glamour in primary care’. Another mentioned that primary care is all about ‘clinical courage’.

I agree. Golden words these, something my young physician friends starting their journey in primary healthcare would do well to remember.

– By Sanjana Brahmawar Mohan, Director, Basic HealthCare Services, is a pediatrician and public health professional. Sanjana holds MBBS and an MD in Pediatrics from University of Rajasthan and has studied Epidemiology from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.